The hot rock hack happened

/I was excited about the World Geothermal Congress this year. (You remember conferences — big, expensive, tiring lecture-marathons that scientists used to go to. But sometimes they were fun.)

Until this year, the WGC has only happened every 5 years and we missed the last one because it was in Australia… and the 2023 edition (it’s moving to a 3-year cycle) will be in China. So this year’s event, just a stone’s throw away in Iceland, was hotly anticipated.

And it still is, because now it will be next May. And we’ll be doing a hackathon there! You should come, get it in your calendar: 27 and 28 May 2021.

Meanwhile, this year… we moved our planned hackathon online. For the record, here’s what happened at the first Geothermal Hackathon.

Logistics: Timezones are tricky

There’s no doubt, the biggest challenge was the rotation of the earth (though admittedly it has other benefits). I believe the safest way to communicate times to a global audience is UTC, so I’ll stick to that here. It’s not ideal for anyone (except Iceland, appropriately enough in this case) but it reduces errors. We started at 0600 UTC and went until about 2100 UTC each day; about 15 hours of fun. I did check in briefly at 0000 UTC on each morning (my evening), in case anyone from New Zealand showed up, but no-one did.

Rob Leckenby and Martin Bentley, both in the UTC+2 zone, handled the early morning hosting, with me, Evan and Diego showing up a few hours later (we’re all in Canada, UTC–a few). This worked pretty well even though, as usual, the hackers were all perfectly happy and mostly self-sufficient whether we were there or not.

Technology-wise, we met up on Zoom, which was good for the start and the end of the day, and also for getting the attention of others in between (many people left the audio open, one ear to the door, so to speak.) Alongside Zoom we used the Software Underground’s Slack. As well as the #geothermal channel, each project had a channel — listed below — which meant that each project could have a separate video meetup at any time, as well as text-based chat and code-sharing. It was a good combination.

Let’s have a look at the hacks.

Six projects

An awesome list for geothermal — #geothermal-awesome — Thomas Martin (Colorado School of Mines), with some input from me and others, made a great start on an ‘awesome list’ document for geothermal, with a machine learning amphasis. He lists papers, tools, and open data. You can read (or contribute to!) the document here.

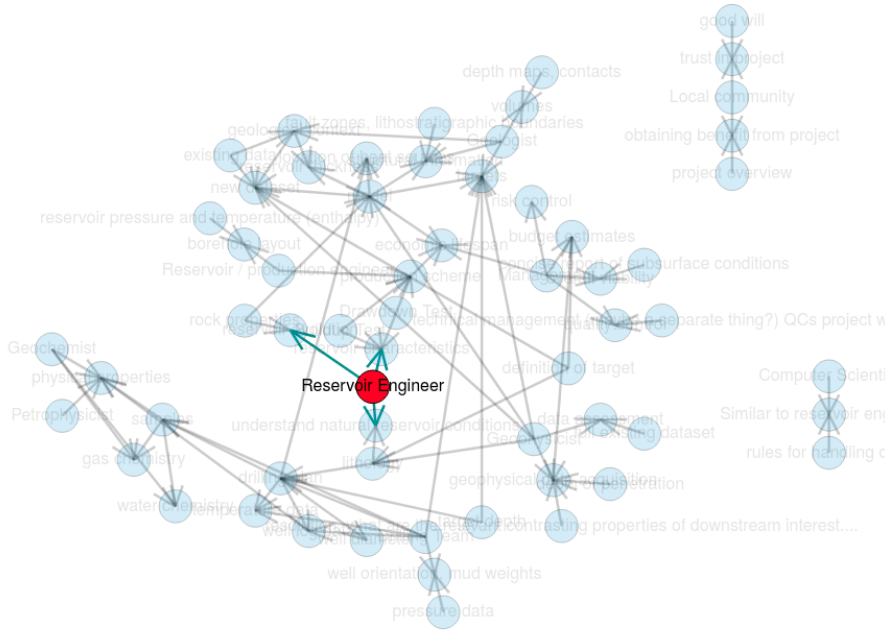

Collaboration tools for geothermal teams — #geothermal-collaboration-tools — Alex Hobé (Uppsala) and Valentin Métraux (GEO2X), with input from Martin Bentley and others, had a clear vision for the event: he wanted to map out the flow of data and interpretations between professionals in a geothermal project. I’ve seen similar projects get nowhere near as far in 2 months as Alex got in 2 days. The team used Holoviews and NetworkX to make some nice graphics.

GEOPHIRES web app — #geothermal-geophires — Marko Gauk (SeisWare) wanted to get into web apps at the event, and he succeeded! He built a web-based form for submitting jobs to a server running GEOPHIRES v2, a ‘full field’ geothermal project modeling tool. You can check out his app here.

Geothermal Natural Language Processing — #geothermal-nlp — Mohammad ‘Jabs’ Aljubran (Stanford), Friso (Denver), along with Rob and me, did some playing with the Stanford geothermal bibliographic database. Jabs and Friso got a nice paper recommendation engine working, while Rob and I managed to do automatic geolocation on the articles — and Jabs turned this into some great maps. Repo is here. Coming soon: a web app.

Experiments with porepy — #geothermal-porepy — Luisa Zuluaga, Daniel Coronel, and Sam got together to see what they could do with porepy, a porous media simulation tool, especially aimed at modeling fractured and deformable rocks.

Radiothermic map of Nova Scotia — #geothermal-radiothermic — Evan Bianco downloaded some open data for Nova Scotia, Canada, to see if he could implement this workflow from Beamish and Busby. But the data turned out to be unscaled (among other things), and therefore probably impossible to use for quantitative purposes. At least he made progress on a nice map.

All in all it was a fun couple of days. You can’t beat a hackathon for leaving behind emails and to-do lists for a day

Except where noted, this content is licensed

Except where noted, this content is licensed