Equinor should change its open data licence

/This is an open letter to Equinor to appeal for a change to the licence used on Volve, Northern Lights, and other datasets. If you wish to co-sign, please add a supportive comment below. (Or if you disagree, please speak up too!)

Open data has had huge impact on science and society. Whether the driving purpose is innovation, transparency, engagement, or something else, open data can make a difference. Underpinning the dataset itself is its licence, which grants permission to others to re-use and distribute open data. Open data licences are licences that meet the Open Definition.

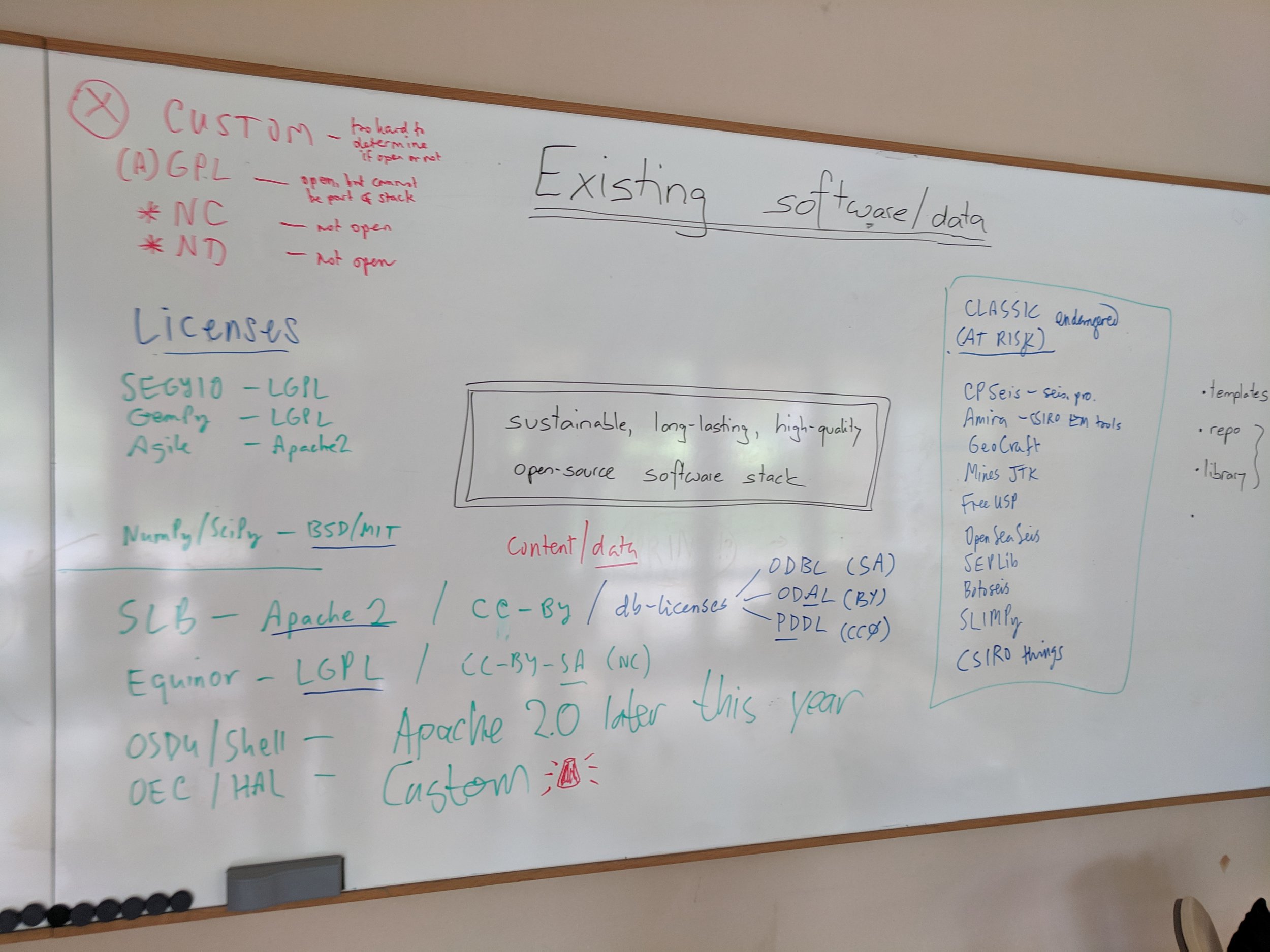

In 2018, Equinor generously released a very large dataset from the decommissioned field Volve. Initially it was released with no licence. Later in 2018, a licence was added but it was a non-open licence, CC BY-NC-SA (open licences cannot be limited to non-commercial use, which is what the NC stands for). Then, in 2020, the licence was changed to a modified CC BY licence, which you can read here.

As far as I know, Volve and other projects still carry this licence. I’ll refer to this licence as “the Equinor licence”. I assume it applies to the collection of data, and to the contents of the collection (where applicable).

There are 3 problems with the licence as it stands:

The licence is not open.

Modified CC licences have issues.

The licence is not clear and exposes licencees to risk of infringement.

Let's look at these in turn.

The licence is not open

The Equinor licence is not an open licence. It does not meet the Open Definition, section 2.1.2 of which states:

“The license must allow redistribution of the licensed work, including sale, whether on its own or as part of a collection made from works from different sources.”

The licence does not allow sale and therefore does not meet this criterion. Non-open licences are not compatible with open licences, therefore these datasets cannot be remixed and re-used with open content. This greatly limits the usefulness of the dataset.

Modified CC licences have issues

The Equinor licence states:

“This license is based on CC BY 4.0 license ”

I interpret this to mean that it is intended to act as a modified CC BY licence. There are two issues with this:

The copyright lawyers at Creative Commons strongly advises against modifying (in particular, adding restrictions to) their licences.

If you do modify one, you may not refer to it as a CC BY licence or use Creative Commons trademarks; doing so violates their trademarks.

Both of these issues are outlined in the Creative Commons Wiki. According to that document, these issues arise because modified licences confuse the public. In my opinion (and I am not a lawyer, etc), the Equinor licence is confusing, and it appears to violate the Creative Commons organization's trademark policy.

Note that 'modify' really means 'add restrictions to' here. It is easier to legally and clearly remove restrictions from CC licences, using the CCPlus licence extension pattern.

The licence is not clear

The Equinor licence contains five restrictions:

You may not sell the Licensed Material.

You must give Equinor and the Volve license partners credit, and provide a link to these terms and conditions, as well as a copyright notice if applicable.

You may not share Adapted Material under a license that prevents recipients from complying with these terms and conditions.

You shall not use the Licensed Material in a manner that appears misleading nor present the Licensed Material in a distorted or incorrect manner.

The license covers all data in the dataset whether or not it is by law covered by copyright.

Looking at the points in turn:

Point 1 is, I believe, the main issue for Equinor. For some reason, this is paramount for them.

Point 2 seems like a restatement of the BY restriction that is the main feature of the CC-BY licence and is extensively described in Section 3.a of that licence.

Point 3 is already covered by CC BY in Section 3.a.4.

Point 4 is ambiguous and confusing. Who is the arbiter of this potentially subjective criterion? How will it be applied? Will Equinor examine every use of the data? The scenario this point is trying to prevent seems already to be covered by standard professional ethics and 'errors and omissions'. It's a bit like saying you can't use the data to commit a crime — it doesn't need saying because commiting crimes is already illegal.

Point 5 is strange. I don’t know why Equinor wants to licence material that no-one owns, but licences are legal contracts, and you can bind people into anything you can agree on. One note here — the rights in the database (so-called 'database rights') are separate from the rights in the contents: it is possible in many jurisdictions to claim sui generis rights in a collection of non-copyrightable elements; maybe this is what was intended? Importantly, Sui generis database rights are explicitly covered by CC BY 4.0.

Finally, I recently received an email communication from Equinor that stated the following:

“[...] nothing in our present licencing inhibits the fair and widespread use of our data for educational, scientific, research and commercial purposes. You are free to download the Licensed Material for non-commercial and commercial purposes. Our only requirement is that you must add value to the data if you intend to sell them on.”

The last sentence (“Our only requirement…”) states that there is only one added restriction. But, as I just pointed out, this is not what the licence document states. The Equinor licence states that one may not sell the licensed material, period. The email states that I can sell it if I add value. Then the questions are, "What does 'add value' mean?", and "Who decides?". (It seems self-evident to me that it would be very hard to sell open material if one wasn't adding value!)

My recommendations

In its current state, I would not recommend anyone to use the Volve or Northern Lights data for any purpose. I know this sounds extreme, but it’s important to appreciate the huge imbalance in the relationship between Equinor and its licensees. If Equinor's future counsel — maybe in a decade — decides that lots of people have violated this licence, what happens next could be quite unjust. Equinor can easily put a small company out of business with a lawsuit. I know that might seem unlikely today, but I urge you to read about GSI's extensive lawsuits in Canada — this is a real situation that cost many companies a lot of money. You can read about it in my blog post, Copyright and seismic data.

When it comes to licences, and legal contracts in general, I believe that less is more. Taking a standard licence and adding words to solve problems you don’t have but can imagine having — and lawyers have very good imaginations — just creates confusion.

I therefore recommend the following:

Adopt an unmodifed CC BY 4.0 licence for the collection as a whole.

Adopt an unmodifed CC BY 4.0 licence for the contents of the collection, where copyrightable.

Include copyright notices that clearly state the copyright owners, in all relevant places in the collection (e.g. data folders, file headers) and at least at the top level. This way, it's clear how attribution should be done.

Quell the fear of people selling the dataset by removing as many possible barriers to using the free version as possible, and generally continuing to be a conspicuous champion for open data.

If Equinor opts to keep a version of the current licence, I recommend at least removing any mention of CC BY, it only adds to the confusion. The Equinor licence is not a CC BY licence, and mentioning Creative Commons violates their policy. We also suggest simplifying the licence if possible, and clarifying any restrictions that remain. Use plain language, give examples, and provide a set of Frequently Asked Questions.

The best path forward for fostering a community around these wonderful datasets that Equinor has generously shared with the community, is to adopt a standard open licence as soon as possible.

Except where noted, this content is licensed

Except where noted, this content is licensed