Is your data digital or just pseudodigital?

/A rite of passage for a geologist is the making of an original geological map, starting from scratch. In the UK, this is known as the ‘independent mapping project’ and is usually done at the end of the second year of an undergrad degree. I did mine on the eastern shore of the Embalse de Santa Ana, just north of Alfarras in Catalunya, Spain. (I wrote all about it back in 2012.)

The map I drew was about as analog as you can get. I drew it with Rotring Rapidograph pens on drafting film. Mistakes had to be painstakingly scraped away with a razor blade. Colour had to be added in pencil after the map had been transferred onto paper. There is only one map in existence. The data is gone. It is absolutely unreproducible.

Digitize!

In order to show you the map, I had to digitize it. This word makes it sound like the map is now ‘digital data’, but it’s really not useful for anything scientific. In other words, while it is ‘digital’ in the loosest sense — it’s a bunch of binary bits in the cloud — it is not digital in the sense of organized data elements with semantic meaning. Let’s call this non-useful format palaeodigital. The lowest rung on the digital ladder.

You can get palaeodigital files from many state and national data repositories. For example, it’s how the Government of Nova Scotia stores its offshore seismic ‘data’ files — as TIFF files representing scans of paper sections submitted by operators. Wiggle trace, obviously, making them almost completely useless.

Protodigital

Nobody draws map by hand anymore, that would be crazy. Adobe Illustrator and (better) Inkscape mean we can produce beautifully rendered maps with about the same amount of effort as the hand-drawn version. But… this still isn’t digital. This is nothing more than a computerized rip-off of the analog workflow. The result is almost as static and difficult to edit as it was on film. (Wish you’d used a thicker line for your fault traces on those 20 maps? Have fun editing those files!)

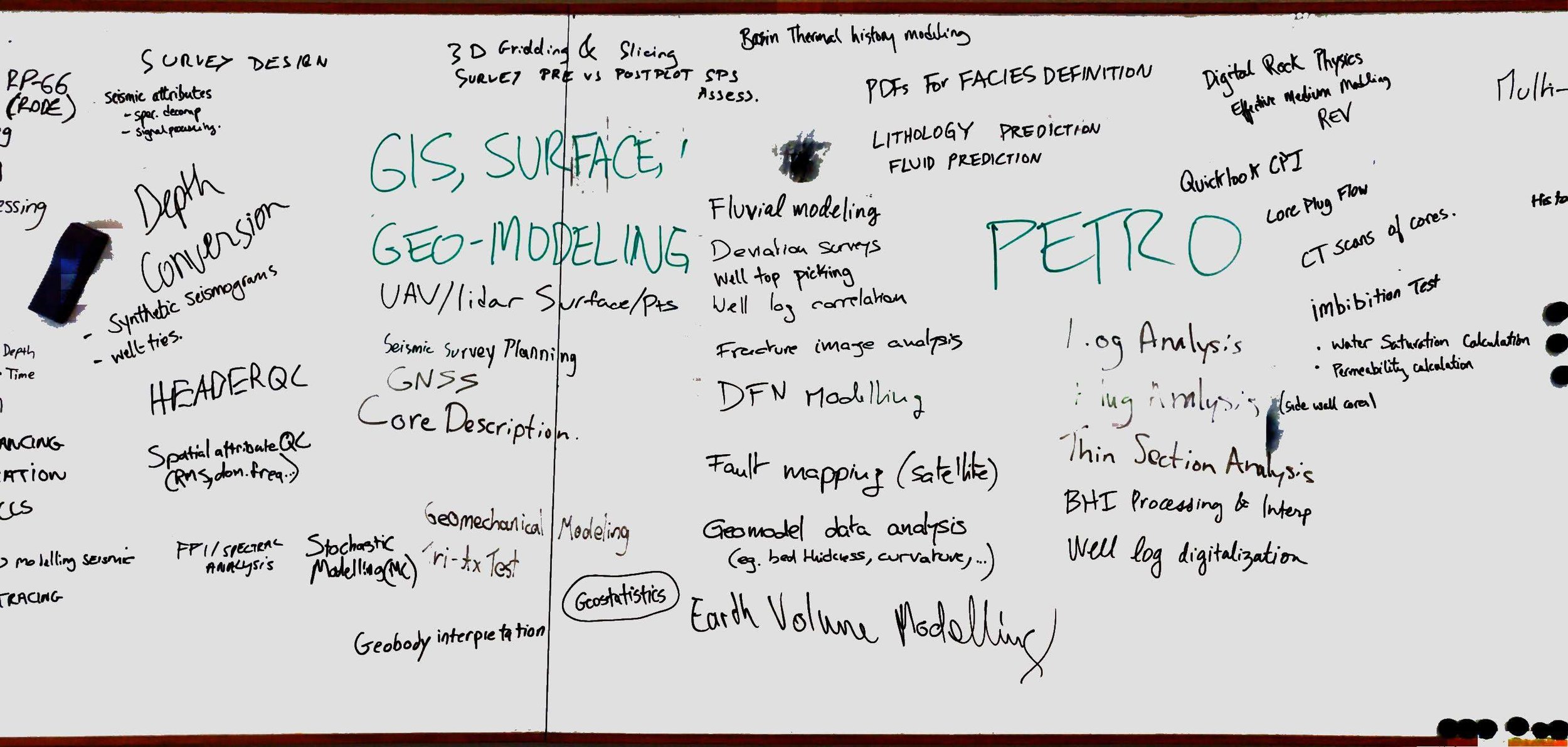

Let’s call the computerization of analog workflows or artifacts protodigital. I’m thinking of Word and Powerpoint. Email. SeisWorks. Techlog. We can think of data in the same way… LAS files are really just a text-file manifestation of a composite log (plus their headers are often garbage). SEG-Y is nothing more than a bunch of traces with a sidelabel.

Together, palaeodigital and protodigital data might be called pseudodigital. They look digital, but they’re not quite there.

(Just to be clear, I made all these words up. They are definitely silly… but the point is that there’s a lot of room between analog and useful, machine-learning-ready digital.)

Digital data

So what’s at the top of the digital ladder? In the case of maps, it’s shapefiles or, better yet, GeoJSON. In these files, objects are described in terms of real geographic parameters, such at latitiude and longitude. The file contains the CRS (you know you need that, right?) and other things you might need like units, data provenance, attributes, and so on.

What makes these things truly digital? I think the following things are important:

They can all be self-documenting…

…and can carry more or less arbitrary amounts of metadata.

They depend on open formats, some text and some binary, that are widely used.

There is free, open-source tooling for reading and writing these formats, usually with reference implementations in major languages (e.g. C/C++, Python, Java).

They are composable. Without too much trouble, you could write a script to process batches of these files, adapting to their content and context.

Here’s how non-digital versions of a document, e.g. a scholoarly article, compare to digital data:

And pseudodigital well logs:

Some more examples:

Photographs with EXIF data and geolocation.

GIS tools like QGIS let us make beautiful maps with data.

Drawing striplogs with a data-driven tool like Python striplog.

A fully-labeled HDF5 file containing QC’d, machine-learning-ready well logs.

Structured, metadata-rich documents, perhaps in JSON format.

Watch out for pseudodigital

Why does all this matter? It matters because we need digital data before we can do any analysis, or any machine learning. If you give me pseudodigital data for a project, I’m going to spend at least 50% of my time, probably more, making it digital before I can even get started. So before embarking on a machine learning project, you really, really need to know what you’re dealing with: digital or just pseudodigital?

Except where noted, this content is licensed

Except where noted, this content is licensed