Reproducibility Zoo

/The Repro Zoo was a new kind of event at the SEG Annual Meeting this year. The goal: to reproduce the results from well-known or important papers in GEOPHYSICS or The Leading Edge. By reproduce, we meant that the code and data should be open and accessible. By results, we meant equations, figures, and other scientific outcomes.

And some of the results are scary enough for Hallowe’en :)

What we did

All the work went straight into GitHub, mostly as Jupyter Notebooks. I had a vague goal of hitting 10 papers at the event, and we achieved this (just!). I’ve since added a couple of other papers, since the inspiration for the work came from the Zoo… and I haven’t been able to resist continuing.

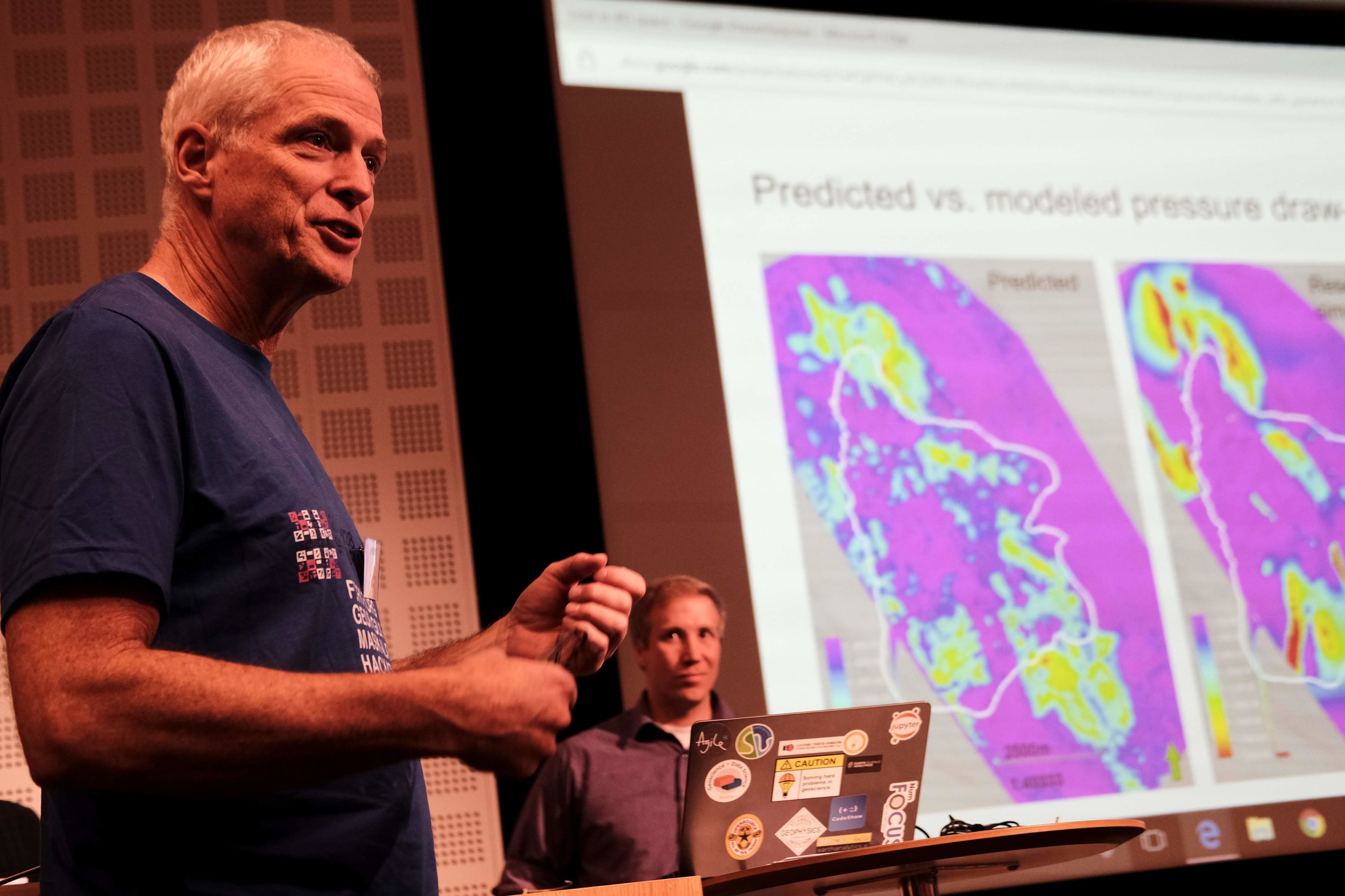

The scene at the Repro Zoo. An air of quiet productivity hung over the booth. Yes, that is Sergey Fomel and Jon Claerbout. Thank you to David Holmes of Dell EMC for the picture.

Here’s what the Repro Zoo team got up to, in alphabetical order:

Aldridge (1990). The Berlage wavelet. GEOPHYSICS 55 (11). The wavelet itself, which has also been added to bruges.

Batzle & Wang (1992). Seismic properties of pore fluids. GEOPHYSICS 57 (11). The water properties, now added to bruges.

Claerbout et al. (2018). Data fitting with nonstationary statistics, Stanford. Translating code from FORTRAN to Python.

Claerbout (1975). Kolmogoroff spectral factorization. Thanks to Stewart Levin for this one.

Connolly (1999). Elastic impedance. The Leading Edge 18 (4). Using equations from bruges to reproduce figures.

Liner (2014). Long-wave elastic attentuation produced by horizontal layering. The Leading Edge 33 (6). This is the stuff about Backus averaging and negative Q.

Luo et al. (2002). Edge preserving smoothing and applications. The Leading Edge 21 (2).

Yilmaz (1987). Seismic data analysis, SEG. Okay, not the whole thing, but Sergey Fomel coded up a figure in Madagascar.

Partyka et al. (1999). Interpretational aspects of spectral decomposition in reservoir characterization.

Röth & Tarantola (1994). Neural networks and inversion of seismic data. Kudos to Brendon Hall for this implementation of a shallow neural net.

Taner et al. (1979). Complex trace analysis. GEOPHYSICS 44. Sarah Greer worked on this one.

Thomsen (1986). Weak elastic anisotropy. GEOPHYSICS 51 (10). Reproducing figures, again using equations from bruges.

As an example of what we got up to, here’s Figure 14 from Batzle & Wang’s landmark 1992 paper on the seismic properties of pore fluids. My version (middle, and in red on the right) is slightly different from that of Batzle and Wang. They don’t give a numerical example in their paper, so it’s hard to know where the error is. Of course, my first assumption is that it’s my error, but this is the problem with research that does not include code or reference numerical examples.

Figure 14 from Batzle & Wang (1992). Left: the original figure. Middle: My attempt to reproduce it. Right: My attempt in red, overlain on the original.

This was certainly not the only discrepancy. Most papers don’t provide the code or data to reproduce their figures, and this is a well-known problem that the SEG is starting to address. But most also don’t provide worked examples, so the reader is left to guess the parameters that were used, or to eyeball results from a figure. Are we really OK with assuming the results from all the thousands of papers in GEOPHYSICS and The Leading Edge are correct? There’s a long conversation to have here.

What next?

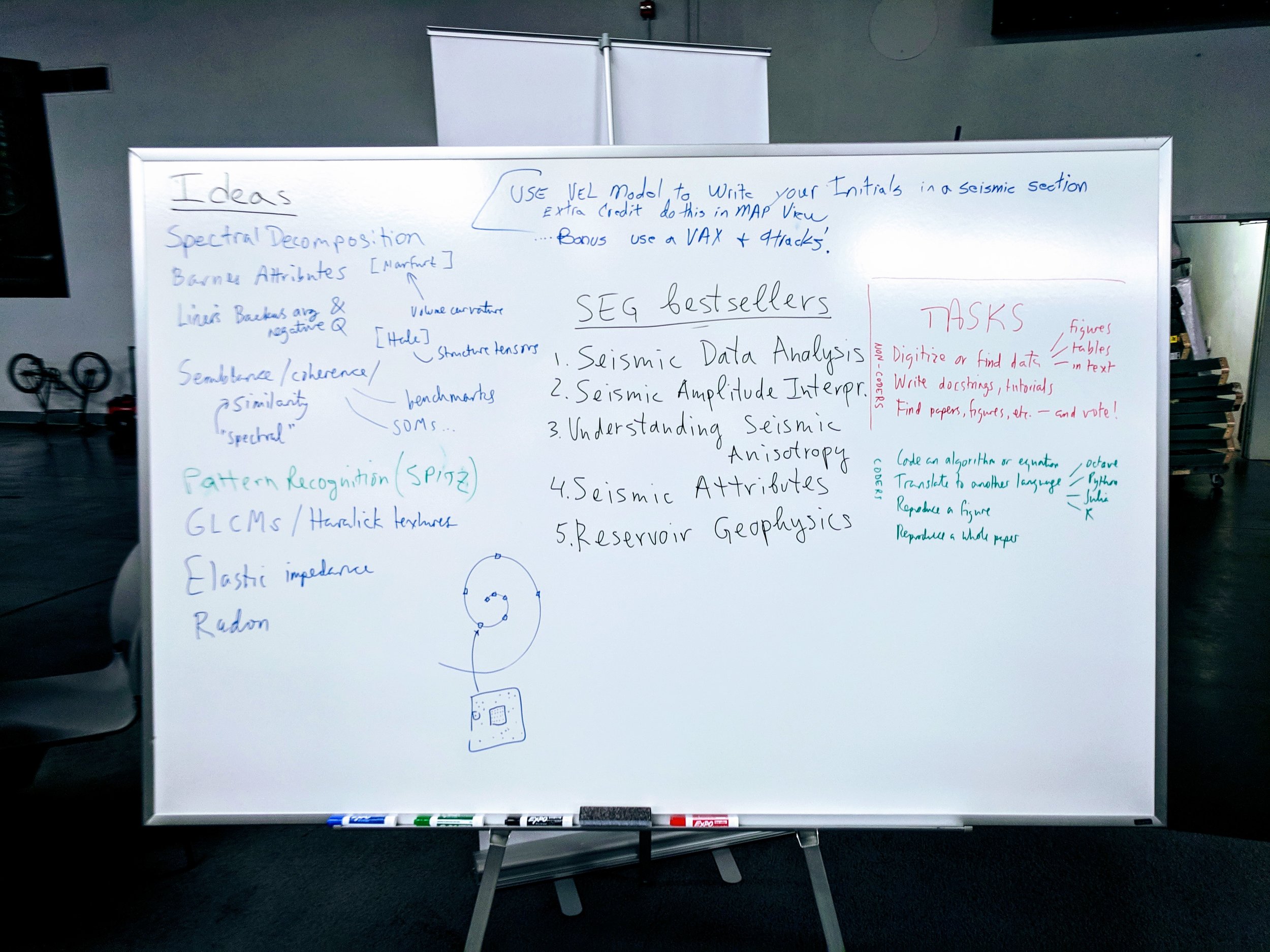

One thing we struggled with was capturing all the ideas. Some are on our events portal. The GitHub repo also points to some other sources of ideas. And there was the Big Giant Whiteboard (below). Either way, there’s plenty to do (there are thousands of papers!) and I hope the zoo continues in spirit. I will take pull requests until the end of the year, and I don’t see why we can’t add more papers until then. At that point, we can start a 2019 repo, or move the project to the SEG Wiki, or consider our other options. Ideas welcome!

Thank you!

The following people and organizations deserve accolades for their dedication to the idea and hard work making it a reality. Please give them a hug or a high five when you see them.

David Holmes (Dell EMC) and Chance Sanger worked their tails off on the booth over the weekend, as well as having the neighbouring Dell EMC booth to worry about. David also sourced the amazing Dell tech we had at the booth, just in case anyone needed 128GB of RAM and an NVIDIA P5200 graphics card for their Jupyter Notebook. (The lights in the convention centre actually dimmed when we powered up our booths in the morning.)

Luke Decker (UT Austin) organized a corps of volunteer Zookeepers to help manage the booth, and provided enthusiasm and coding skills. Karl Schleicher (UT Austin), Sarah Greer (MIT), and several others were part of this effort.

Andrew Geary (SEG) for keeping things moving along when I became delinquent over the summer. Lots of others at SEG also helped, mainly with the booth: Trisha DeLozier, Rebecca Hayes, and Beth Donica all contributed.

Diego Castañeda got the events site in shape to support the Repro Zoo, with a dashboard showing the latest commits and contributors.

Except where noted, this content is licensed

Except where noted, this content is licensed