Open source geoscience is _________________

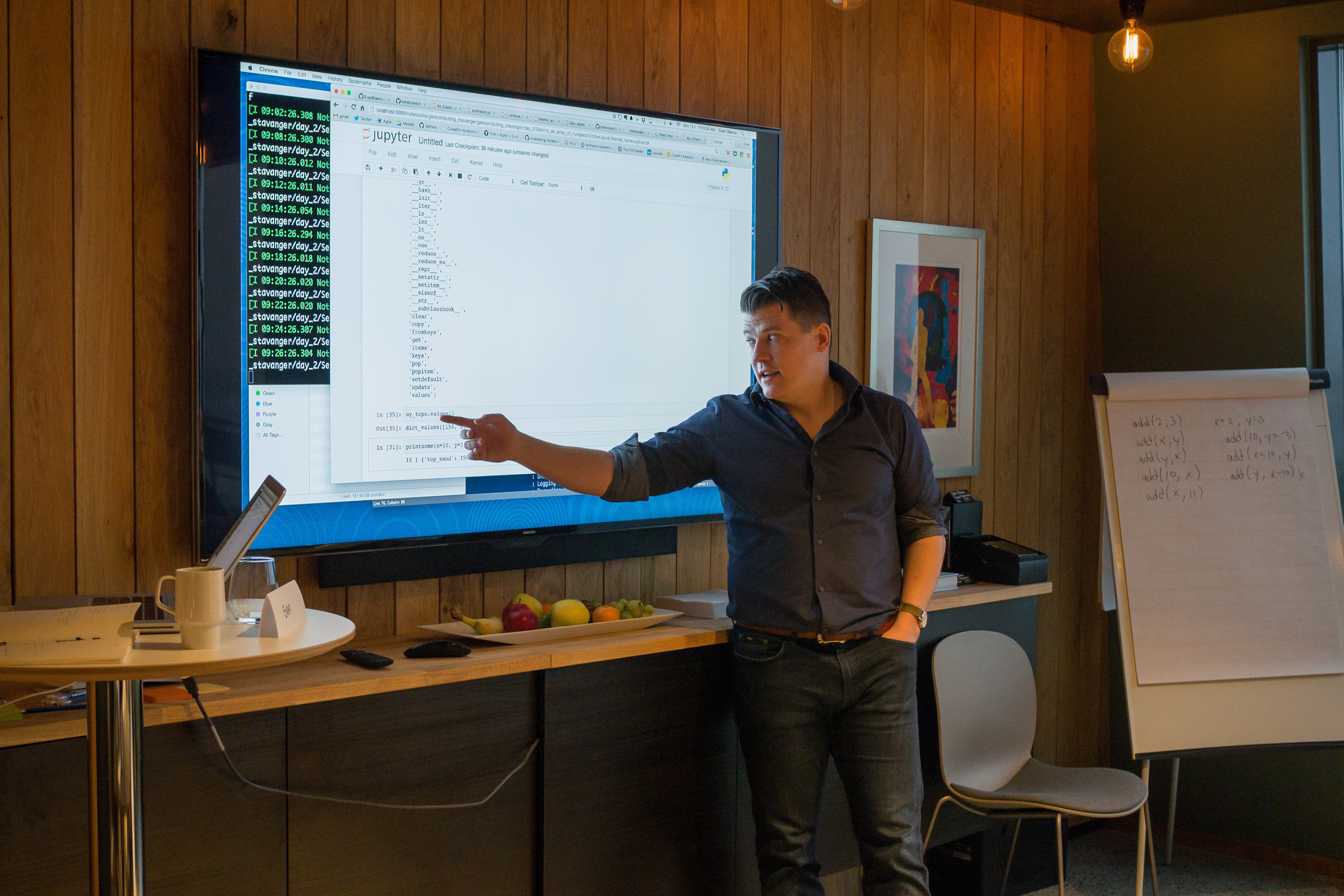

/As I wrote yesterday, I was at the Open Source Geoscience workshop at EAGE Vienna 2016 on Monday. Happily, the organizers made time for discussion. However, what passes for discussion in the traditional conference setting is, as I've written before, stilted.

What follows is not an objective account of the proceedings. It's more of a poorly organized collection of soundbites and opinions with no real conclusion... so it's a bit like the actual discussion itself.

TL;DR The main take home of the discussion was that our community does not really know what to do with open source software. We find it difficult to see how we can give stuff away and still make loads of money.

I'm not giving away my stuff

Paraphrasing a Schlumberger scientist:

Schlumberger sponsors a lot of consortiums, but the consortiums that will deliver closed source software are our favourites.

I suppose this is a way to grab competitive advantage, but of course there are always the other consortium members so it's hardly an exclusive. A cynic might see this position as a sort of reverse advantage — soak up the brightest academics you can find for 3 years, and make sure their work never sees the light of day. If you patent it, you can even make sure no-one else gets to use the ideas for 20 years. You don't even have to use the work! I really hope this is not what is going on.

I loved the quote Sergey Fomel shared; paraphrasing Matthias Schwab, his former advisor at Stanford:

Never build things you can't take with you.

My feeling is that if a consortium only churns out closed source code, then it's not too far from being a consulting shop. Apart from the cheap labour, cheap resources, and no corporation tax.

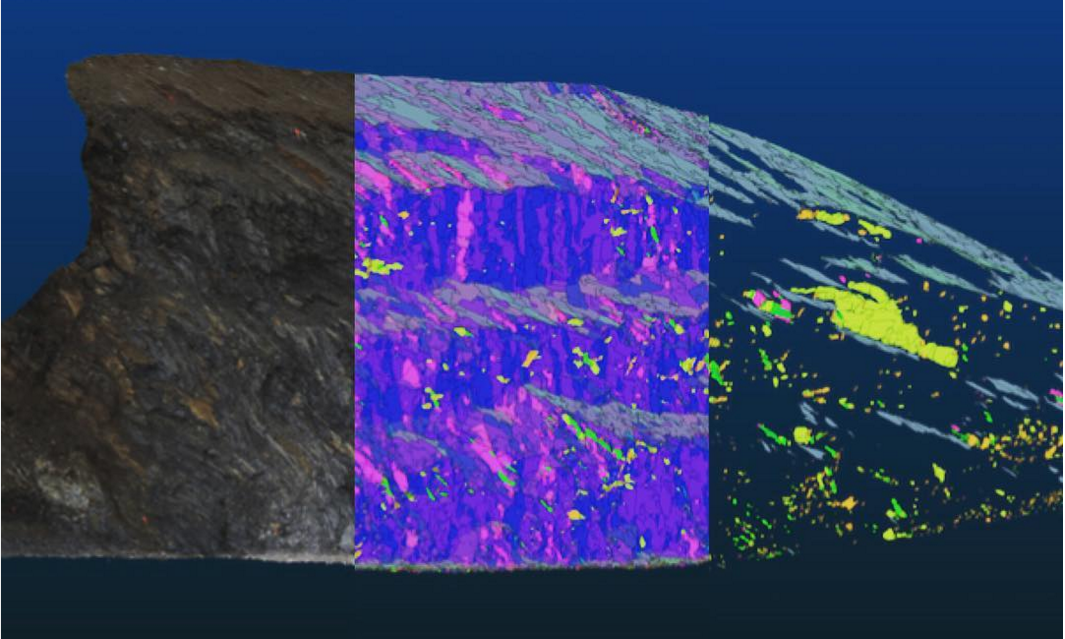

Yesterday, in the talks in the main stream, I asked most of the presenters how people in the audience could go and reproduce, or simply use, their work. The only thing that was available was a commerical OpendTect plugin of dGB's, and one free-as-in-beer MATLAB utility. Everything else was unavailble for any kind of inspection, and in one case the individual would not even reveal the technology framework they were using.

Support and maintenance

Paraphrasing a Saudi Aramco scientist:

There are too many bugs in open source, and no support.

The first point is, I think, a fallacy. It's like saying that Wikipedia contains inaccuracies. I'd suggest that open source code has about the same number of bugs as proprietary software. Software has bugs. Some people think open source is less buggy; as Linus Torvalds said: "Given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow." Kristofer Tingdahl (dGB) pointed out that the perceived lack of support is a business opportunity for open source community. Another participant mentioned the importance of having really good documentation. That costs money of course, which means finding ways for industry to support open source software development.

The same person also said something like:

[Open source software] changes too quickly, with new versions all the time.

...which says a lot about the state of application management in many corporations and, again, may represent opportunity rather than a threat to open source movement.

Only in this industry (OK, maybe a couple of others) will you hear the impassioned cry, "Less change!"

The fog of torpor

When a community is falling over itself to invent new ways to do things, create new value for people, and find new ways to get paid, few question the sharing and re-use of information. And by 'information' I mean code and data, not a few PowerPoint slides. Certainly not all information, but lots. I don't know which is the cause and which is the effect, but the correlation is there.

In a community where invention is slow, on the other hand, people are forced to be more circumspect, and what follows is a cynical suspicion of the motives of others. Here's my impression of the dynamic in the room during the discussion on Monday, and of course I'm generalizing horribly:

- Operators won't say what they think in front of their competitors

- Vendors won't say what they think in front of their customers and competitors

- Academics won't say what they think in front of their consortium

customerssponsors - Students won't say what they think in front of their advisors and potential employers

This all makes discussion a bit stilted. But it's not impossible to have group discussions in spite of these problems. I think we achieved a real, honest conversation in the two Unsessions we're done in Calgary, and I think the model we used would work perfectly in all manner of non-technical and in technical settings. We just have to start doing it. Why our convention organizers feel unable to try new things at conferences is beyond me.

I can't resist finishing on something a person at Chevron said at the workshop:

I'm from Chevron. I was going to say something earlier, but I thought maybe I shouldn't.

This just sums our industry up.

Except where noted, this content is licensed

Except where noted, this content is licensed