Pick This! Social interpretation

/PIck This is a new web app for social image interpretation. Sort of Stack Exchange or Quora (both awesome Q&A sites) meets Flickr. You look for an interesting image and offer your interpretation with a quick drawing. Interpretations earn reputation points. Once you have enough rep, you can upload images and invite others to interpret them. Find out how others would outline that subtle brain tumour on the MRI, or pick that bifurcated fault...

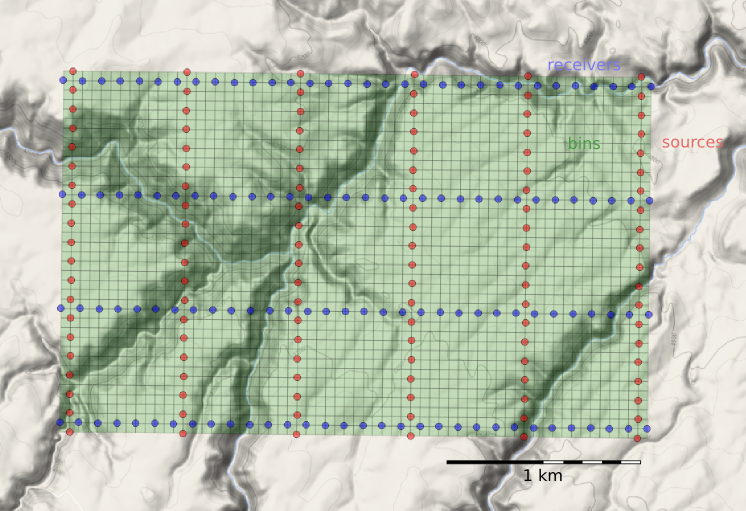

A section from the Penobscot 3D, offshore Nova Scotia, Canada. Overlain on the seismic image is a heatmap of interpretations of the main fault by 26 different interpreters. The distribution of interpretations prompts questions about what is 'the' answer. Pick this image yourself at pickthis.io.

The app was born at the Geophysics Hackathon in Denver last year. The original team consisted of Ben Bougher, a UBC student and long-time Agile collaborator, Jacob Foshee, a co-founder of Durwella, Chris Chalcraft, a geoscientist at OpenGeoSolutions, Agile's own Evan Bianco of course, and me ordering pizzas and googling domain names. By demo time on Sunday afternoon, we had a rough prototype, good enough for the audience to provide the first seismic interpretations.

Getting from prototype to release

After the hackathon, we were very excited about Pick This, with lots of ideas for new features. We wanted it to be easy to upload an image, being clear about its provenance, and extremely easy to make an interpretation, right in the browser. After some great progress, we ran into trouble bending the drawing library, Raphael.js, to our will. The app languished until Steve Purves, an affable geoscientist–programmer who lives on a volcano in the middle of the Atlantic, came to the rescue a few days ago. Now we have something you can use, and it's fun! For example, how would you pick this unconformity?

This data is proprietary to MultiKlient Invest AS. Licensed CC-BY-SA.

This beautiful section is part of this month's Tutorial in SEG's The Leading Edge magazine, and was the original inspiration for the app. The open access essay is by Don Herron, the creator of Interpreter Sam, and describes his approach to interpreting unconformities, using this image as the partially worked example. We wanted a way for readers to try the interpretation themselves, without having to download anything — it's always good to have a use case before building something new.

What's next for Pick This?

I'm really excited about the possibilities ahead. Apart from the fun of interpreting other people's data, I'm especially excited about what we could learn from the tool — how long do people spend interpreting? How many edits do they make before submitting? And we'd love to add other modes to the tool, like choosing between two image enhancement results, or picking multiple features. And these possibilities only multiply when you think about applications outside earth science, in medical imaging, remote sensing, or astronomy. So much to do, so little time!

We trust your opinion. Maybe you can help us:

- Is Pick This at all interesting or fun or useful to you? Is there a use case that occurs to you?

- Making the app better will take time and therefore money. If your organization is interested in image enhancement, subjectivity in interpretation, or machine learning, then maybe we can work together. Get in touch!

Whatever you do, please have a look at Pick This and let us know what you think.

Except where noted, this content is licensed

Except where noted, this content is licensed